Apollo 9 astronaut. (Photo from Nicolas M. Short,NASA

The Atlantic and Gulf Coasts play an important role in both the economic value and natural history of the United States. Hundreds of ports, including major cities such as New York, Boston, Jacksonville, Charleston, Miami, Tampa, Norfolk, and New Orleans thrive because of international and domestic trade along these coasts. The coastline represents over 50% of the country's urban population (NOAA, 2004) and attracts countless tourists throughout the year from all over the globe. Historic value also comes into play as much of the nation’s battles for independence and civil rights were fought along the Eastern seaboard. Extending from Texas to Maine, the coast is an integral part of the national and global infrastructure, but the coasts are more than just sand and waves. The dunes, deltas and barrier islands that form the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts are features of a landscape that have endured millions of years of being molded, shaped, and reworked by natural forces. These coasts represent some of nature's finest work and a perpetually changing environment. The Atlantic and Gulf Coasts are passive margins, meaning they are unaffected by tectonic processes. However, the coasts are not without important and powerful processes that continually work towards a stable equilibrium. Coastal storms supply the energy to erode, transport, and deposit sediments along the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts. This persistent movement of sediments by the winds and waves and other geologic processes have created the beaches and barrier islands that we enjoy today.

Coastal Geology

of the United States. NOAA Coastal Services Center

The Atlantic and Gulf Coasts stretch from Maine to Texas and consist of a series of beaches, river deltas, marshes, barrier islands, and, in the Northeast, rocks and gravel. The coasts are impacted by the underlying geologic history and formation that varies along the stretch of coastline. Characteristics of today’s beaches have been shaped by surface water runoff, changes in sea level, and storm events, but the Atlantic and Gulf coastal plains remain the central features of the coast. While the two geological provinces share some similarities, they are inherently different.

Both coastal plains consist of marine sediments that were deposited, cemented, uplifted, and are now tilted toward the sea (click here for more information on these processes). Varying sea levels lead to the accumulation of sediments that form both the underlying sedimentary rocks and the sand found on beaches.

The sediments of the Gulf coastal plain originate as far north as southern Illinois, traveling down the Mississippi River to the Gulf. Both coastal plains are underlain by unconsolidated sand and mud, but the Gulf coastal plain has an added component, cohesive mud. Though the coasts are rooted in the same formation events, the modern geologic differences can be attributed to the presence of the Mississippi Delta in the Gulf coastal plain. Here, the Mississippi River deposits fine-grained mud that is held together by cohesive forces (click here to read more about cohesive forces). These small sediments along with the abundant limestone in the Southeast lead to fine-grained beaches and saltwater marshes along the Gulf coast.

The Atlantic coastal plain sediments originate in the Hudson River watershed in New York, traveling as far south as southern Florida. This coastal plain and drainage system is immediately affected by the Appalachian Mountains. Both glacial and fluvial erosion of the relatively old Appalachian Mountain Chain has produced the Atlantic coastal plain over millions of years through sediment accumulation. Sediments eroded from the mountains are carried toward the ocean by streams and rivers and are deposited at various points along the way. On average, the Atlantic Coast receives more intense waves than the Gulf because the Atlantic Coast experiences more direct storm impacts, contributing to the two regions’ differences in geology.

Eastern seaboard.

Beaches & Barrier Islands

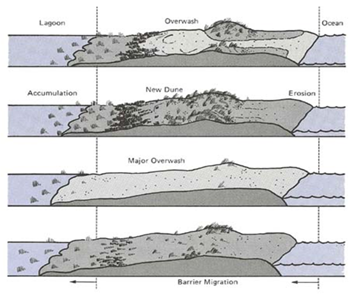

A chain of over 300 barrier islands exist along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of North America. These islands are bodies of sand that run parallel to the coast, the peaks of which are above water level, creating a divide between ocean and mainland. The formation of Atlantic and Gulf Coast beaches and barrier islands has been 2,000,000 years in the making. Sea level has been fluctuating within a range of about 100 meters during this period, causing the shoreline in some places to migrate over 200 kilometers landward. As the shore retreated, it carried sediments with it that provided the basis for our contemporary barrier islands.

Although there is evidence of a great number of sea level changing events over the past 2,000,000 years, the event that most greatly contributed to the landscape we see today began about 18,000 years ago. At that time, the glaciers that covered most of North America reached further south than ever before, and the sea level was 100 meters below its current state. A change in the global energy budget caused the massive glaciers to start melting and the sea level rose 1-2 cm per year for about 14,000 years, more than 5 times the current rate of sea level rise (Parker, 1992). Less than 6,000 years ago, the sea level rate of change slowed to less than 2 mm per year (NOAA), allowing natural forces such as wind and waves to begin forming the sandy beaches we see today.

The sediment that had accumulated from previous sea level change events was reworked by waves, winds, and storms; the mechanisms responsible for sea level rise and fall, sediment transport, and accumulation of sand have been in place for millennia, but the landscape we are familiar with today is only about 5,000 years old.

The sediment that had accumulated from previous sea level change events was reworked by waves, winds, and storms; the mechanisms responsible for sea level rise and fall, sediment transport, and accumulation of sand have been in place for millennia, but the landscape we are familiar with today is only about 5,000 years old.

As the glaciers melted and sea level rose, the fine sediments that had been deposited at river deltas and disbursed along the coast were pushed inland. These sediments, continually pushed landward by the rising sea, eventually accumulated to form the barrier islands. Today, the rate of sea level rise is increasing and we can expect that these natural processes that have created the beautiful barrier islands of the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts will continue to alter these environments. The barrier islands that have become such high areas of human activity including commercial, residential, and tourist use will continue their landward retreat with the rising sea level.

Parker, Bruce B. (1992). Sea level as an Indicator of Climate and Global Change. Marine Technology Society Journal, 25 (4). Retrieved from http://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/sltrends/mtsparker.html.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Coastal Services Center. Beach Nourishment: A Guide for Local Government Officials. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.csc.noaa.gov/beachnourishment/html/geo/barrier.htm.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). (2004). Population Trends Along the Coastal United States: 1980 – 2008. Washington, DC: Crosset, Kristen M, Culliton.

Thomas J, Goodspeed, Timothy R, & Wiley, Peter C. Retrieved from http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/programs/mb/pdfs/coastal_pop_trends_complete.pdf